Coding Style

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How should I organise my code?

What are some practical steps I can take to improve the quality and readability of my scripts?

What tools exist to help me follow good coding style?

Objectives

write and adjust code to follow standards of style and organisation.

use a linter to check and modify their code to follow PEP8.

provide sufficient documentation for their functions and scripts.

Credit Where It’s Due dept.

A lot of the content in this section summarises the material in this book chapter, which provides a much more comprehensive overview of style considerations and gives recommendations for reviewing other people’s code.

Up to now you’ve been learning new tools and skills to help you write more powerful programs with Python. Now we’re going to spend a little time discussing how you can write better code with Python.

Why is Style Important?

At some stage, all this cool code you’re writing is probably going to be read by someone who doesn’t know/remember all the context in which it was written - a collaborator, your supervisor, someone reading the code you published with your latest paper, you in another six months’ time. There are some things you can be doing now to help make it as easy as possible for people to read and understand your programs in the future.

Computers don’t care if code makes any sense: as long as it’s syntactically valid, they’ll run it anyway. (This point will ring sadly true to anyone who’s ever accidentally filled all the disk space on their computer with the output from a poorly-designed script.) Humans, on the other hand, do care. If they’re going to be able to use your software in their research, contribute to/help maintain your code base, or assess your previous work to decide whether or not to hire you, it can make a big difference whether or not your code is well-documented and easily readable.

Code readability is one of the big advantages of Python as a language, making it particularly well-suited to research software, which users should be more interested in reading and understanding than e.g. the source code of their web browser. With this in mind, our considerations of code style will focus on maximising code readability but some of the tools we’ll discuss here will also identify issues relating to the performance of the code itself.

5.1. Words Between the Lines of Age

Given an input string and a substring length, the function

count_frequenciesreturns counts of substrings found in the input string. An additional parameter is used to determine whether the counted substrings should overlap or not.from collections import defaultdict def count_frequencies(s, w, o): counts = defaultdict(int) if o: step = 1 else: step = w for i in range(0, len(s), step): word = s[i:i+w] if len(word) < w: return counts counts[word] += 1 return countsYou are allowed to make only one of the following changes to the function:

- Rename the input variables

s,w, ando- Add a docstring to the function

- Set default values for one or more of the input parameters

- Insert comments to annotate the function definition

Which do you think is the most important change to make? Pair up and explain your choice to your partner. Did you both make the same choice? If not, did you find your partner’s justification convincing?

Solution

Here are some suggested benefits for each choice:

- Renaming the variables, perhaps to something like

input_string,word_length, andoverlapping, would make the purpose (and, in two cases at least, the expected type) of each of the function’s arguments much clearer. It is much more likely that someone seeing this function for the first time would understand what was going on with variable names like these.- Adding a comprehensive docstring for the function would allow users to check how to use it via Python’s built-in

help, or via various features of their chosen IDE (e.g. Jupyter users could typecount_frequencies?and get a pop-up usage message). You can write as much detail as you like into the docstring, so this is probably the most comprehensive option!- Default values can help make the purpose of the functions’ arguments clearer, e.g.

o=Truetells the user that this option is a logical switch. Furthermore, if all but one of a function’s arguments has a default value, and the user knows what kind of object the function expects to operate on, it’s less likely they will need to check the documentation/signature of the function. (Which, in this case, would be A Good Thing because it wouldn’t be much help!)- Comments can be really helpful for someone reading the source code of the function, to help them understand what each line is doing. You’re also not limited in how many comments you can insert, so this option would allow you to be very thorough! However, these comments aren’t visible to anyone trying to work with your function e.g. calling

help(count_frequencies)after loading it from a module, so it’s not the most user-friendly option. All the options given are valid choices and, thankfully, in reality you’re unlikely to ever need to choose between them! The authors would choose option 1 because good, self-explanatory variable names go a long way to making your code self-documenting.

PEP 8

Whenever we join a new community, it is often confusing and intimidating to try to figure out the social norms and standards we should follow to “integrate,” fit in, and be accepted. There are things the established members can do to make their community welcoming and inclusive, like follow a Code of Conduct, provide a guide for new contributors and templates for issues and pull/merge requests, and acknowledge and support first-time contributions, but it’s also the responsibility of the newcomer to follow the standards set by the community.

Luckily, the Python community agreed on a set of standards quite early on. Referred to as PEP 8 after the Python Enhancement Proposal in which the standards were first agreed, it includes guidelines and recommendations on how to write, organise, and document your Python code.

When in Rome…

PEP 8 is the standard for all core Python code, such as modules in the standard library, and is the default for Python projects more generally. However, different communities and projects may have conventions and standards that differ from PEP 8. As we’ll discuss again later, the most important thing is consistency within a project so, if you want to contribute to an existing project it’s best to find out which standards are being used there and follow those. Similarly, if you’re setting up a new project or bringing in collaborators for the first time, it’s best to discuss and agree on your code style guidelines. You can then include these in your contributors guide.

Layout

PEP 8 provides extensive guidance on how your code should be laid out. Below are the key points.

Indentation

Use spaces for indentation, instead of tab characters. Use four spaces to mark each level of indentation in your programs. Avoiding tab characters makes code look more consistent between systems, which may vary considerably in the way they display tab characters.

Most text editors can be configured to insert spaces when you press Tab or when they automatically indent for you while you’re coding.

Maximum line length

Try to keep your lines to ≤79 characters in length. Docstrings should be kept to 72 characters or fewer. Exceptions can be made where splitting the code across two lines would make it less readable.

The code block below demonstrates a strategy you can use to reduce the length of lines.

# implied line continuation:

# split definitions inside (), [], and {} across multiple lines

# using indentation to make clear how the lines are all part

# of the same definition

class_sizes = {"Archaeology": [10, 12, 7],

"Biology": [14, 19, 17],

"French Literature": [9, 6, 9],

"Linguistics": [12, 15, 16],

"Political Science": [8, 11, 10]}

# when using implied line continuation, split lines before binary operators

final_score = (points_round_1

+ points_round_2

+ points_round_3

- cards_remaining

- fair_play_penalty)

Blank lines

Place two blank lines above and below top-level functions and class definitions, e.g.

import pandas as pd

def plot_rolling_mean_cases(df, country):

"""Draw a line plot of the rolling mean of daily reported cases,

given a DataFrame object containing the following columns:

* countriesAndTerritories: country/territory names (str)

* dateRep: dates on which cases were recorded (datetime)

* cases: the number of cases reported on each day (int)

:param df: the dataframe to operate on

:type df: pandas.core.frame.DataFrame

:param country: the name of the country to plot data for

:type country: str

"""

# note the use of extra () below to allow us to split

# the chain of pandas methods across multiple lines...

(df[df['countriesAndTerritories']==country]

.set_index('dateRep')

['cases']

.rolling(7)

.mean()

.plot(kind='line'))

def get_days(date):

"""Return the number of days represented within a timestamp."""

return date.days

[...]

Imports

All imports must be at the top of the file (only the “shebang” line, encoding information, and module-level docstring should come before them) and should be on separate lines, except where a handful of things are being imported from the same location, e.g.

from sys import argv, stdin, stdout

# put a blank line between standard library and third-party imports

import numpy

import pandas

Don’t use wildcard imports (e.g. from sys import *).

Instead, be explicit about which components will be used throughout the script.

Whitespace

PEP 8 devotes a lot of space to discussion of the acceptable use of whitespace. Here are the most important points.

# no extraneous spaces immediately inside () [] or {}

current_members = ['David', 'Nigel', 'Derek', 'Jeffery', 'Gregg'] # good

sponge_cake = [ 'flour', 'butter', 'eggs', 'sugar', 'vanilla' ] # bad

# no extraneous spaces immediately before , ; or :

def swap_values(a, b): # good

c = a ; a = b ; b = c # bad

return (a, b)

# no space immediately before opening () in a function or method call

x = 20

y = 10

z = 0

x, y = swap_values(a, b) # good

z, x = swap_values (z, x) # bad

# (this rule also applies to [] in slicing or indexing)

# space after keywords

# 'return', 'if', 'elif' are keywords and so:

if(condition and condition): # bad

if (condition and condition): # good

if condition and condition: # better

return (a, b) # good - a tuple is returned

return(a) # bad - 'a' is returned

return a # good - 'a' is returned

# don't use spaces to align assignments, even if you think it looks neater

cats = 2 # good

dogs = 3 # bad

ducks = 9

There are a lot more rules about whitespace - check the main PEP 8 page for the full list and more examples.

Trailing Commas

If you want to create a tuple containing only one value, you must include a trailing comma, i.e.

single_value_tuple = (ducks,)

But you might wish to include them voluntarily elsewhere,

e.g. to indicate where a collection of values is expected to

increase over time.

If you do this,

don’t include an extra space between the trailing comma

and the closing ), ], or },

and place each value on its own line with appropriate indentation, i.e.

# good

genome_files = [

'H_sapiens.fasta',

'P_troglodytes.fasta',

'G_gorilla.fasta',

]

# bad

genome_files = ['H_sapiens.fasta', 'P_troglodytes.fasta', 'G_gorilla.fasta',]

Comments

Hopefully this is not the first time that you’ve been told this, but annotating your code with comments where necessary is a very good idea. Useful comments should tell the reader why the code is written this way, and sometimes what the code is doing. For example, it might be useful to add a comment explaining what that number 10 is that appeared out of nowhere. The how should usually be something you get by reading the code.

Comments should begin with a single space after the #.

Multi-line or block comments should begin like this on every line,

with paragraphs separated by a single # (no trailing space).

Some editors use ''' or """ to delimit multi-line comments in Python.

These, however, are not actual comments as the content of a multi-line string

is still interpreted by the compiler, even if not assigned to a variable.

An example of ''' and """ not being ignored are documentation strings.

There is a whole separate PEP devoted to documentation strings (docstrings). PEP 8 limits itself to the two most important points:

- Write docstrings for all modules, functions, classes, and methods that are “public-facing”. That is, which might be used by someone else at some point.

- The closing

"""of the triple-quoted docstring should be on a line of its own.

5.2. Fashions Change. Style is Forever.

Look at the following three code blocks. (Based on this script from the Matplotlib Example Gallery).

Block A

def hinton(matrix, max_weight=None, ax=None): """Draw Hinton diagram for visualizing a weight matrix.""" ax = ax if ax is not None else plt.gca() if not max_weight: max_weight = 2 ** np.ceil(np.log(np.abs(matrix).max()) / np.log(2)) ax.patch.set_facecolor('gray') ax.set_aspect('equal', 'box') ax.xaxis.set_major_locator(plt.NullLocator()) ax.yaxis.set_major_locator(plt.NullLocator()) for (x,y), w in np.ndenumerate(matrix): color = 'white' if w > 0 else 'black' size = np.sqrt(np.abs(w) / max_weight) rect = plt.Rectangle([x - size/2, y - size/2], size, size, facecolor=color, edgecolor=color) ax.add_patch(rect)Block B

def hinton(matrix, max_weight=None, ax=None): """Draw Hinton diagram for visualizing a weight matrix.""" ax = ax if ax is not None else plt.gca() if not max_weight: max_weight = 2 ** np.ceil(np.log(np.abs(matrix).max()) / np.log(2)) ax.patch.set_facecolor('gray') ax.set_aspect('equal', 'box') ax.xaxis.set_major_locator(plt.NullLocator()) ax.yaxis.set_major_locator(plt.NullLocator()) for (x, y), w in np.ndenumerate(matrix): color = 'white' if w > 0 else 'black' size = np.sqrt(np.abs(w) / max_weight) rect = plt.Rectangle([x - size / 2, y - size / 2], size, size, facecolor=color, edgecolor=color) ax.add_patch(rect)Block C

def hinton (matrix,max_weight=None,ax=None) : """Draw Hinton diagram for visualizing a weight matrix.""" ax=ax if ax is not None else p.gca() if not max_weight: max_weight=2**np.ceil(np.log(np.abs(matrix).max())/np.log(2)) ax.patch.set_facecolor('gray') ax.set_aspect('equal','box') ax.xaxis.set_major_locator(plt.NullLocator()) ax.yaxis.set_major_locator(plt.NullLocator()) for (x,y),w in np.ndenumerate(matrix): color = 'white' if w>0 else 'black' size = np.sqrt(np.abs(w)/max_weight) rect = plt.Rectangle([x-size/2,y-size/2],size,size,facecolor=color,edgecolor=color) ax.add_patch(rect)

- Which block conforms to the standards described in PEP8?

- Is it also the block you find easiest to read?

- In each block, mark the lines/places where you consider the style to be problematic (that is, where the [lack of] style actively makes the code difficult to read/inaccessible in some other way).

- Pair up and compare your notes with a partner’s. Did you both identify the same problems?

Solution

Block B conforms to PEP 8.

Code Checkers

In its entirity, PEP 8 is quite long. The section above only covered a fraction of the guidelines it lays out. When you’re busy writing code it’s easy to miss an infraction, or forget one of the standards. (There are probably a lot of them in the code examples in these lesson materials - if you spot any, please tell us about them!)

Thankfully, tools exist to help us with this. Code checkers - tools usually run on the command line, which can tell us where our code doesn’t comply with PEP 8 - allow us to focus our creative energy on writing code to solve a problem or run the analysis we want to work on, and worry about fixing issues with style later.

Broadly speaking, we can divide code checkers (often also referred to as linters) into two categories: those that read code and report the problems they find, leaving it up to us to fix these, and those that directly modify the code to enforce compliance themselves.

We’ll begin by looking at three different code checkers,

pycodestyle, pylint, pyflakes,

that fall into the first category.

pycodestyle

pycodestyle used to be called pep8,

and checks code against most of the

conventions described in PEP 8.

An example of usage is given below.

$ pycodestyle code/readings_02.py

code/readings_02.py:4:1: E302 expected 2 blank lines, found 1

The tool found one issue with the code in this file.

The output tells us where the problem is (position 1 on line 4),

and gives a code (E302) and a message describing the issue:

that the function definition beginning on line 4

wasn’t preceded by two blank lines.

pyflakes

pyflakes is a lot more permissive with style than pycodestyle:

it is more interested in finding technical problems in the code

of the file it’s checking.

To see the difference between this approach and that used by pycodestyle,

let’s run pyflakes on the same file we used above.

$ pyflakes code/readings_02.py

code/readings_02.py:5: local variable 'script' is assigned to but never used

So pyflakes didn’t notice the missing blank line

before the function definition,

but did highlight where a variable was being created on line 5

but never used

(which is inefficient from a memory and processing perspective

or could be due to a typo later in the script).

If you care most about performance -

you want your code (and your code checks!) to be fast -

pyflakes is a good choice.

Another code checker, flake8,

combines pyflakes with pycodestyle in a single PEP 8 style-checker.

The companion website flake8rules provides examples

for every offending rule in pycodestyle and pyflakes.

pylint

The third and final code checker we’ll introduce is pylint.

Rather than providing an introductory blurb,

let’s dive right into trying it out on our example file:

$ pylint code/readings_02.py

************* Module readings_02

code/readings_02.py:1:0: C0114: Missing module docstring (missing-module-docstring)

code/readings_02.py:4:0: C0116: Missing function or method docstring (missing-function-docstring)

code/readings_02.py:5:4: W0612: Unused variable 'script' (unused-variable)

-----------------------------------

Your code has been rated at 7.00/10

Once again, we haven’t been reprimanded on the lack of a second blank line

before the function definition.

But pylint highlights three problems -

two missing docstrings and the assigned-but-never-used variable

also flagged up by pyflakes -

and actually gives our code a grade!

(7.00/10 is not bad,

given that pylint is capable of assigning negative scores to scripts!)

pylint, like pyflakes and pycodestyle is configurable

by allowing you to ignore or silence some of the rules, globally or per-project.

However, pylint also allows you to add your own rules for it to check.

This can be useful to follow a particular project’s style guide instead of the PEP 8 standard.

Choices

So you may have noticed that all of these code checkers identified different problems with the example program, in some cases without any overlap between the lists of things they told us to fix. (This might feel eerily familiar to anyone who had a paper peer-reviewed recently…)

In fact, there exist a great many more code checkers/linters than the three described here. We recommend this comparison if you’d like to learn more about what your options are.

Tattoo Everything

A tool that falls into the second category we mentioned above is

black. Named after famous quote from Henry Ford,blackdoesn’t only check code, it actively enforces PEP 8 compliance by modifying code to fit the style guide.

blackis becoming popular, particularly for large Python projects, because it can be deployed as part of their continuous integration pipeline i.e. code can be automatically adjusted to comply with the syle guide as part of the set of automated tests and other actions triggered when new code is pushed to the code base. This saves time that might be spent on minor style changes and discussions during the development process. (Note that the developers would like you to know thatblackis still considered a beta product.)

5.3. Comparing Different Code Checkers

Analyse the code below with

pycodestyle,pylint, andpyflakes, using default settings in each case. (You can download the script here.)def find_anagrams(words,ignore_case = True) : anagrams = [] if ignore_case == True: charsets = [ set(w.lower()) for w in words ] return [w for w in words if charsets.count(set(w.lower())) > 1] else: charsets = [ set(w) for w in words ] return [w for w in words if charsets.count(set(w)) > 1] test_words = "back to the time when trouble was not always on our minds No mite item".split() print(find_anagrams(test_words, ignore_case=False))What differences do you notice in the output? How many different types of problem do these tools find in the code? Use the information provided by these tools to guide you while you fix our code. Is there anything that you think could be improved in the code, which wasn’t picked up by any of the code-checking tools used above?

Solution

The expected output of each tool is included below:

$ pycodestyle anagrams.pyanagrams.py:1:24: E231 missing whitespace after ',' anagrams.py:1:36: E251 unexpected spaces around keyword / parameter equals anagrams.py:1:38: E251 unexpected spaces around keyword / parameter equals anagrams.py:1:44: E203 whitespace before ':' anagrams.py:3:20: E712 comparison to True should be 'if cond is True:' or 'if cond:' anagrams.py:4:21: E201 whitespace after '[' anagrams.py:4:51: E202 whitespace before ']' anagrams.py:7:21: E201 whitespace after '[' anagrams.py:7:43: E202 whitespace before ']' anagrams.py:10:1: E305 expected 2 blank lines after class or function definition, found 1 anagrams.py:10:80: E501 line too long (93 > 79 characters)$ pylint anagrams.py************* Module anagrams anagrams.py:1:23: C0326: Exactly one space required after comma def find_anagrams(words,ignore_case = True) : ^ (bad-whitespace) anagrams.py:1:36: C0326: No space allowed around keyword argument assignment def find_anagrams(words,ignore_case = True) : ^ (bad-whitespace) anagrams.py:1:44: C0326: No space allowed before : def find_anagrams(words,ignore_case = True) : ^ (bad-whitespace) anagrams.py:4:19: C0326: No space allowed after bracket charsets = [ set(w.lower()) for w in words ] ^ (bad-whitespace) anagrams.py:4:51: C0326: No space allowed before bracket charsets = [ set(w.lower()) for w in words ] ^ (bad-whitespace) anagrams.py:7:19: C0326: No space allowed after bracket charsets = [ set(w) for w in words ] ^ (bad-whitespace) anagrams.py:7:43: C0326: No space allowed before bracket charsets = [ set(w) for w in words ] ^ (bad-whitespace) anagrams.py:1:0: C0114: Missing module docstring (missing-module-docstring) anagrams.py:1:0: C0116: Missing function or method docstring (missing-function-docstring) anagrams.py:3:4: R1705: Unnecessary "else" after "return" (no-else-return) anagrams.py:3:7: C0121: Comparison to True should be just 'expr' (singleton-comparison) anagrams.py:2:4: W0612: Unused variable 'anagrams' (unused-variable) -------------------------------------------------------------------- Your code has been rated at -3.33/10$ pyflakes anagrams.pyanagrams.py:2: local variable 'anagrams' is assigned to but never used

pylintprovides the most comprehensive list of issues with the example code, including a warning about the unused variable, as well as flagging up the issues involving whitespace and redundancy in the comparison withTruethatpycodestyleidentified. Unlike either of the other two tools,pylintalso noticed that the function didn’t include a docstring.An issue that wasn’t identified by any of the three code checkers is the repetition in the

charsets = [...]lines.charsets = [ set(w.lower()) for w in words ] # <--- return [w for w in words if charsets.count(set(w.lower())) > 1] else: charsets = [ set(w) for w in words ] # <---One rule of good coding is Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY): multiple lines containing (almost) identical code are usually a sign of an inefficient program.

A cleaned-up version of our program, addressing all of the problems identified above, might look like this:

''' A module of tools for finding anagrams in lists of strings. ''' def find_anagrams(words, ignore_case=True): ''' Find all anagrams within a list of strings. Parameters: words: a list of strings to be filtered ignore_case: if True, treat equivalent characters in upper and lowercase (e.g. 'A' and 'a') as matching. (default: True) Returns: If any anagrams were found, a list containing those strings. Otherwise, an empty list. ''' if ignore_case: text_transform = str.lower else: text_transform = str charsets = [set(text_transform(w)) for w in words] return [w for w in words if charsets.count(set(text_transform(w))) > 1] test_words = """ back to the time when trouble was not always on our minds No mite item""".split() print(find_anagrams(test_words, ignore_case=False))

Documentation

Docstrings were briefly mentioned during the discussion of PEP 8 above. You can, and should, write them at the module level (i.e. at the beginning of a file) and at the function level.

Docstrings are beneficial to anyone reading your source code,

where they work like a multiline comment to describe the purpose and

usage of the code,

and for anyone trying to use it in their programs.

Python’s built-in help function will display the docstring

of whatever function, class, or module it is passed.

"""A collection of functions to plot case data by country/territory."""

import pandas as pd

def plot_rolling_mean_cases(df, country):

"""Draw a line plot of the rolling mean of daily reported cases,

given a DataFrame object containing the following columns:

* countriesAndTerritories: country/territory names (str)

* dateRep: dates on which cases were recorded (datetime)

* cases: the number of cases reported on each day (int)

:param df: the dataframe to operate on

:type df: pandas.core.frame.DataFrame

:param country: the name of the country to plot data for

:type country: str

"""

(df[df['countriesAndTerritories']==country]

.set_index('dateRep')

['cases']

.rolling(7)

.mean()

.plot(kind='line'))

def get_days(date):

"""Return the number of days represented within a timestamp."""

return date.days

help(plot_rolling_mean_cases)

Help on function plot_rolling_mean_cases in module __main__:

plot_rolling_mean_cases(df, country)

Draw a line plot of the rolling mean of daily reported cases,

given a DataFrame object containing the following columns:

* countriesAndTerritories: country/territory names (str)

* dateRep: dates on which cases were recorded (datetime)

* cases: the number of cases reported on each day (int)

:param df: the dataframe to operate on

:type df: pandas.core.frame.DataFrame

:param country: the name of the country to plot data for

:type country: str

As we mentioned before, PEP 257 provides extensive information

on docstring style standards.

Another tool, sphinx,

also provides a guide on suggested format.

This is interesting because,

if you follow this guidance when writing your docstrings,

sphinx can automatically create rendered documentation pages as HTML or even as a PDF,

ready for you to publish as an online reference for users.

Plugins also exist for some development environments

that can help make writing docstrings easier and faster.

Good Jupyter Hygiene

We’ll finish with some additional guidance for the Jupyter users in the audience. The authors of this lesson agree that Jupyter Notebooks are an amazing tool for computational research. However, it’s also true that the platform can permit or even encourage bad practice when used carelessly. Here are a few good practices we suggest you adopt when working with Jupyter Notebooks/Lab:

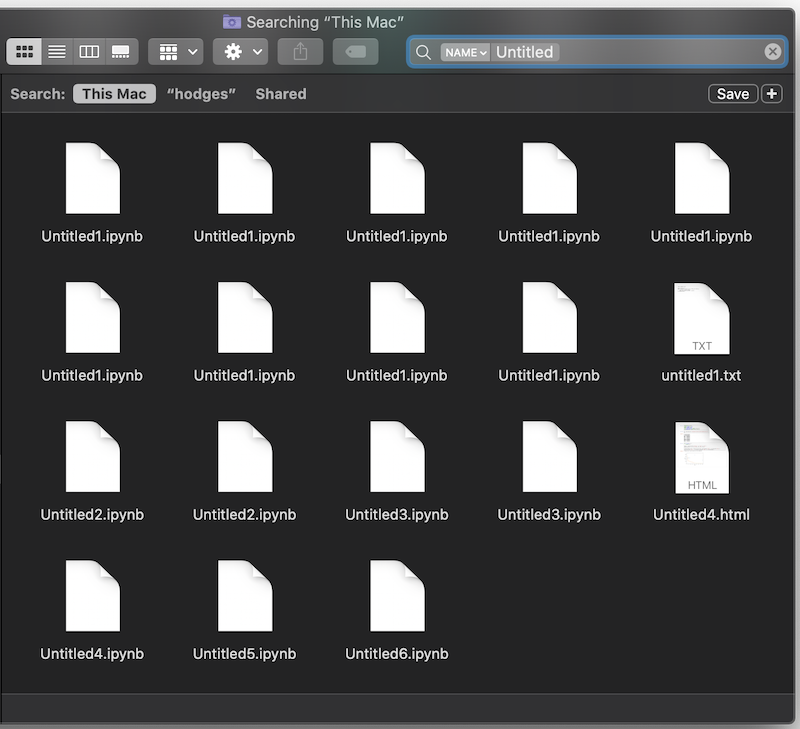

- When you begin a new notebook, give it a name before you do anything else!

- Use comments & Markdown to annotate what you’re doing, even when you think there’s no way you could possibly forget the context or be confused by the code later.

- Be careful with cell order: the way that Jupyter allows cells to arbitrarily run and re-run at any location in the file makes it easy to get mixed up, to overwrite a result, and to make bad assumptions about what value/type a variable has. It’s also very easy to lose track of the steps you took to make a figure.

- Related to the point above, make use of the “Run all”/”Run all above” features. These will keep you honest with the ordering of your cells, and help to make sure that all the necessary processing steps have been done before you get excited about producing a final result.

- Clear all the output from your notebook before saving the

.ipynbfile. This also helps to enforce good practices in cell ordering, and helps (at least a little) with line-by-line version comparison (diffing) e.g. for projects under version control - this measure also helps minimizing repository growth due to images/plots embedded in the notebook. If you want to keep a version that includes the output from executed cells, export the notebook as static HTML, which has the added advantage of being more easily shareable with colleagues.- if you’re interested in keeping notebooks under version control, we recommend you check out

nbdime.

- if you’re interested in keeping notebooks under version control, we recommend you check out

Key Points

It is easier to read and maintain scripts and Jupyter notebooks that are well organised.

The most commonly-used style guide for Python is detailed in PEP8.

Linters such as

pycodestyleandblackcan help us follow style standards.The rules and standards should be followed within reason, but exceptions can be made according to your best judgement.